P Clot Trial

- The CLOT trial, from McMaster University, was published in NEJM in 2003. This landmark trial sought to address whether long-term anticoagulation with subcutaneous dalteparin offered benefit compared to oral anticoagulation in the cancer population in preventing recurrent VTE.

- Background Patients with cancer have a substantial risk of recurrent thrombosis despite the use of oral anticoagulant therapy. We compared the efficacy of a low-molecular.

PubMed • Full text • PDF

- 6Population

- 8Outcomes

Clinical Question

O'Hara NN, Degani Y, Marvel D, Wells D, Mullins CD, Wegener S, Frey K, Joseph T, Hurst J, Castillo R, O'Toole RV; PREVENT CLOT Stakeholder Committee. Which orthopaedic trauma patients are likely to refuse to participate in a clinical trial? A latent class analysis. 2019 Oct 11;9(10):e032631. Doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-032631.

In patients with cancer and acute symptomatic VTE, how does LMWH compare with warfarin in preventing VTE recurrence?

Bottom Line

P Clot Trial Test

In patients with cancer, dalteparin reduced VTE recurrence without increasing bleeding risk or deaths compared to warfarin.

Major Points

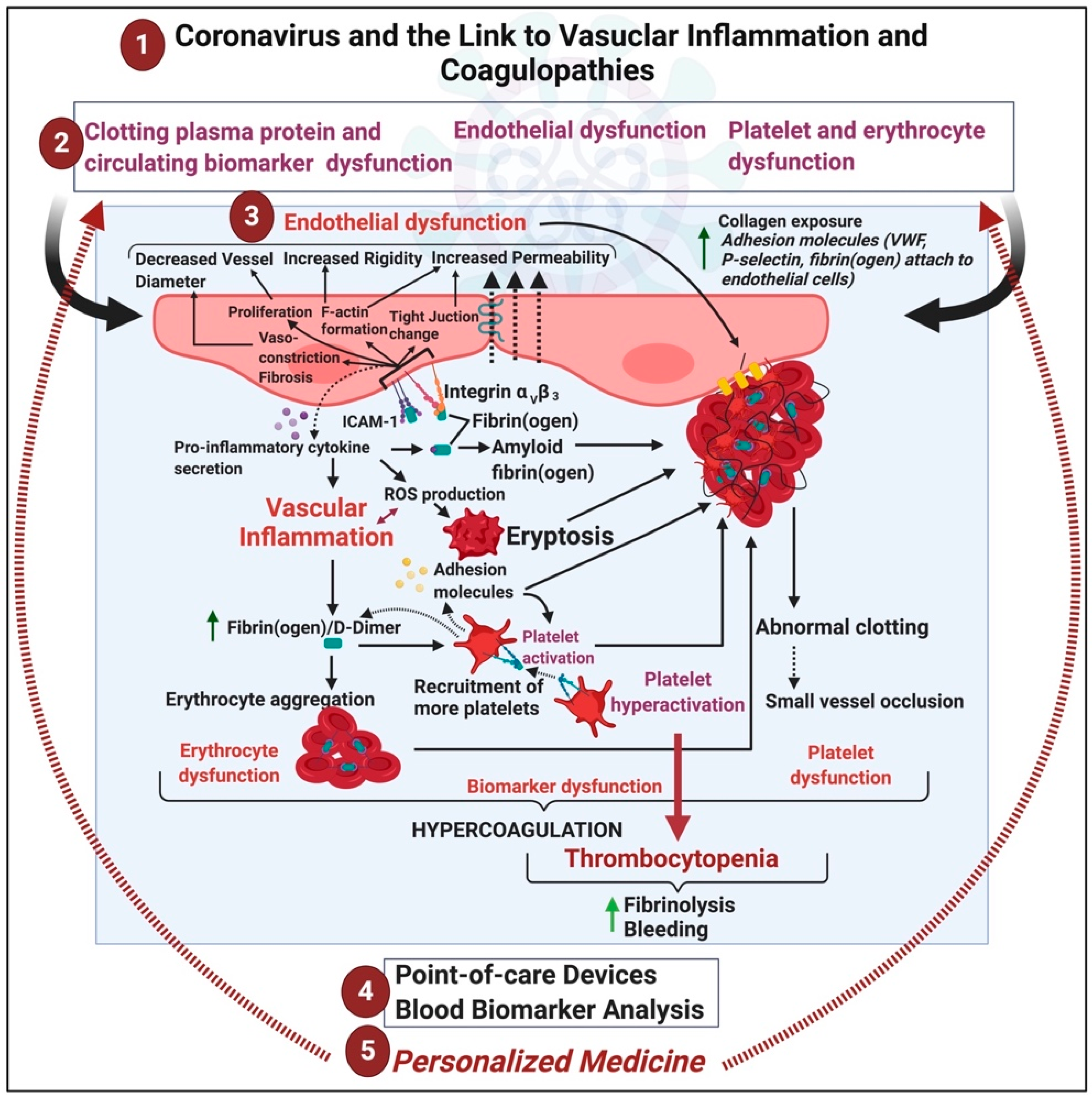

Prior to the CLOT trial, standard therapy for venous thromboembolism (VTE) consisted of a brief period of unfractionated heparin or low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) followed by long-term oral anticoagulation. The 2003 Comparison of Low Molecular Weight Heparin Versus Oral Anticoagulant Therapy for Long Term Anticoagulation in Cancer Patients With Venous Thromboembolism (CLOT) trial demonstrated superiority of dalteparin (LMWH) over oral anticoagulants among patients with cancer. Dalteparin was associated with a reduction in the rate of recurrent VTE at 6 months without any significant differences in the rate of bleeding or mortality as compared with warfarin. These findings were confirmed in the 2006 LITE[1] and ONCENOX[2] trials.

Despite the clinical evidence, adoption of LMWH for VTE in the setting of malignancy has been slow because of the considerable cost of the therapy.[3] However, this cost may be at least somewhat offset by reduction in high-cost care related to acute thromboses.[4]

A pooled subgroup analysis of other RCTs found rivaroxaban to be similar to vitamin K antagonist therapy for secondary prevention of VTE in patients with cancer.[5]

The 2018 Hokusai VTE Cancer Trial showed edoxaban to be non-inferior to dalteparin in an open label study.

Guidelines

ACCP Antithrombotic Therapy for VTE Disease (2016, adapted): [6]

- In patients with DVT of the leg or PE and no cancer, as long-term (first 3 months) anticoagulant therapy, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, or edoxaban are recommended over vitamin K antagonist (VKA) therapy (all Grade 2B)

- In patients with DVT of the leg or PE and cancer (“cancer-associated thrombosis”), as long-term (first 3 months) anticoagulant therapy, LMWH is recommended over other agents (Grade 2C)

- In patients with DVT of the leg or PE who receive extended therapy, recommend no need to change the choice of anticoagulant after the first 3 months (Grade 2C)

- In patients who have recurrent VTE on VKA therapy (in the therapeutic range) or on dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, or edoxaban (and are believed to be compliant), recommend switching to treatment with LMWH at least temporarily (Grade 2C).

- In patients with an unprovoked DVT of the leg (isolated distal or proximal) or PE, we recommend treatment with anticoagulation for at least 3 months over treatment of a shorter duration (Grade 1B), and we recommend treatment with anticoagulation for 3 months over treatment of a longer, time-limited period (eg, 6, 12, or 24 months) (Grade 1B).

- In patients with a first VTE that is an unprovoked proximal DVT of the leg or PE and who have a (i) low or moderate bleeding risk (see text), we suggest extended anticoagulant therapy (no scheduled stop date) over 3 months of therapy (Grade 2B), and a (ii) high bleeding risk (see text), we recommend 3 months of anticoagulant therapy over extended therapy (no scheduled stop date) (Grade 1B).

- In patients with a second unprovoked VTE and who have a (i) low bleeding risk (see text), we recommend extended anticoagulant therapy (no scheduled stop date) over 3 months (Grade 1B); (ii) moderate bleeding risk (see text), we suggest extended anticoagulant therapy over 3 months of therapy (Grade 2B); or (iii) high bleeding risk (see text), we suggest 3 months of anticoagulant therapy over extended therapy (no scheduled stop date) (Grade 2B).

- In patients with DVT of the leg or PE and active cancer (“cancer-associated thrombosis”) and who (i) do not have a high bleeding risk, we recommend extended anticoagulant therapy (no scheduled stop date) over 3 months of therapy (Grade 1B), and (ii) have a high bleeding risk, we suggest extended anticoagulant therapy (no scheduled stop date) over 3 months of therapy (Grade 2B).

- In patients with an unprovoked proximal DVT or PE who are stopping anticoagulant therapy and do not have a contraindication to aspirin, we suggest aspirin over no aspirin to prevent recurrent VTE (Grade 2B).

Design

- Multicenter, open-label, parallel-group, randomized, controlled trial

- N=676 patients with cancer and acute symptomatic VTE

- LMWH (n=338)

- Oral anticoagulation (n=338)

- Setting: 48 clinical centers in 8 countries

- Enrollment: 1999-2001

- Mean follow-up: 125 days (LMWH) and 115 days (oral anticoagulation)

- Analysis: Intention-to-treat

- Primary outcome: Recurrent VTE

Population

Inclusion Criteria

- Adult patients

- Active cancer, defined as:

- any cancer other than basal cell or squamous cell carcinoma of skin within 6 months prior to enrollment,

- any treatment for cancer within the prior 6 months, or

- recurrent or metastatic cancer

- Newly diagnosed, symptomatic proximal deep vein thrombosis (popliteal or more proximal veins based upon ultrasound or contrast venography), pulmonary embolism (by CT angiogram, V/Q scan, or pulmonary angiogram), or both

Exclusion Criteria

- Weight <40kg

- ECOG (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group) status 3 or 4

- Receipt of therapeutic heparin for more than 48h before randomization

- Receipt of oral anticoagulant therapy

- Active or serious bleeding within prior 2 weeks

- Conditions associated with high bleeding risk (active peptic ulcer disease, recent neurosurgery, etc.)

- Thrombocytopenia (<75k)

- Contraindications to heparin such as HIT

- Use of contrast medium

- Creatinine >3 times the upper limit of the normal range

- Pregnancy

Baseline Characteristics

From the LMWH group.

- Demographics: Age 62 years, female sex 53%

- ECOG score:

- 0. 24%

- 1. 40%

- 2. 35%

- 3. 1%

- Enrolled before protocol amended to exclude ECOG 3-4

- Outpatient: 50%

- Inpatient: 50%

- Hematologic cancer: 12%

- Solid tumor disease: No clinical disease 11%, localized only 12%, metastatic 66%

- Chemo, XRT, or surgery: 79%

- Current smoker: 10%

- History of DVT/PE: 12%

- Recent major surgery: 18%

- Central line: 14%

- Type of VTE: DVT 70%, PE 30%

Interventions

- Randomized to dalteparin (LMWH) or warfarin

- Dalteparin group treated with 200 IU/kg/day SQ for 1 month followed by 150 IU/kg/day for the subsequent 5 months

- Measuring anti-Xa levels discouraged except in patients with renal insufficiency

- Dose held for platelets <50k and adjusted for platelets 50-100k

- Max dose 18,000 IU/day

- Oral anticoagulation group treated with warfarin (acenocoumarol in Spain and Netherlands)

- Goal INR 2-3 except for platelets 50-100k, in which goal INR was 1.5-2.5

Outcomes

Comparisons are LMWH vs. oral anticoagulation.

Primary Outcome

- Recurrent VTE

- Defined as recurrent DVT, nonfatal PE, or fatal PE.

- 8.0% vs. 15.8% (HR 0.48; 95% CI 0.30-0.77; P=0.002)

- DVT only: 14 vs. 37 events

- Nonfatal PE: 8 vs. 9 events

- Fatal PE: 5 vs. 7 events

Secondary Outcomes

- Bleeding

- Major: 6% vs. 4% (P=0.27)

- Any: 14% vs. 19% (P=0.09)

P Clot Trial Definition

- Mortality

- 39% vs. 41% (P=0.53)

Criticisms

- Patients in the oral anticoagulant group had an INR above goal 24% of the time[7]

- Unclear how compliant patients will be with subcutaneous injections in clinical practice[7]

- No cost analysis[7]

Funding

Funding provided by Pharmacia, Peapack, NJ, which also supplied the study drug.

Further Reading

- ↑Hull RD, et al. 'Long-term low-molecular-weight heparin versus usual care in proximal-vein thrombosis patients with cancer.' American Journal of Medicine. 2006;119(12):1062-1072.

- ↑Deitcher SR, et al. 'Secondary prevention of venous thromboembolic events in patients with active cancer: Enoxaparin alone versus initial enoxaparin followed by warfarin for a 180-day period.' Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2006;12(4):389-396.

- ↑Linkins Lori-Ann. 'Management of venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer: Role of dalteparin.' Vascular health and risk management. 2008;4(2):279-287.

- ↑Bick RL. 'Perspective: Cancer-associated thrombosis.' The New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;349:109-111.

- ↑Prins MH, et al. 'Oral rivaroxaban versus enoxaparin with vitamin K antagonist for the treatment of symptomatic venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer (EINSTEIN-DVT and EINSTEIN-PE): A pooled subgroup analysis of two randomised controlled trials.' The Lancet Haematology. 2014;1(1):e37-e46.

- ↑Kearon C et al. Antithrombotic Therapy for VTE Disease: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest 2016. 149:315-52.

- ↑ 7.07.17.2Multiple authors. 'Correspondence: Dalteparin compared with an oral anticoagulant for thromboprophylaxis in patients with cancer.' The New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;349:1385-1387.

The ATTRACT Study was a large clinical trial that compared two commonly-used DVT treatment strategies (blood-thinning medications alone or blood-thinning medication plus catheter-directed clot removal) to determine which is best. This landmark multi-disciplinary initiative was strongly endorsed by the Office of the U.S. Surgeon General because of the study goal to improve patient outcomes, a key research priority noted in the Surgeon General’s Call to Action on DVT.

Why Was the ATTRACT Trial Performed?

The ATTRACT Trial addressed a major controversy among doctors regarding the best way to treat patients with proximal deep vein thrombosis (DVT, blood clots of the upper leg and pelvis). It was known that even when standard blood-thinning drugs are used, about 40% of patients will develop post-thrombotic syndrome (PTS). Because PTS results from permanent damage to the leg veins that is caused by the blood clots, some doctors have urged their immediate removal by a procedure that delivers clot-busting drugs and devices, in addition to blood thinning-drugs.

On the other hand, the clot-busting drugs can cause bleeding, and there were no well-designed, large studies showing that these new treatments truly improved patient health in the long run.

So, the main reason why the ATTRACT Trial was performed was to determine if eliminating blood clots with these procedures was effective in preventing PTS, with acceptable safety and costs. Because PTS is a common problem that affects many thousands of patients each year, the ATTRACT Trial was hailed as a landmark study, and its conduct was strongly endorsed by multiple health professional organizations and the Office of the United States Surgeon General.

What Is the Current Status of the Study?

The ATTRACT Trial successfully enrolled its full target of 692 patients and closed to enrollment on December 16, 2014. The 2-year patient follow-up period was completed for the last patient in early 2017. The study’s main results were presented at the Society of Interventional Radiology’s Annual Scientific Meeting in Washington, D.C., on March 6, 2017, and were subsequently published in the New England Journal of Medicine on December 7, 2017. As of mid-2018, the study’s Steering Committee is continuing to analyze the data and write secondary manuscripts.

Main Study Results

Among patients with acute DVT, the addition of pharmacomechanical catheter directed thrombolysis (the clot-busting treatment) to blood-thinning medications (anticoagulants) did not result in a lower risk of PTS but did result in a higher risk of major bleeding, so it should not be used as routine first-line treatment for DVT. However, the clot-busting treatment improved recovery from DVT (reduced leg pain and swelling), and also reduced the severity of PTS – these benefits were mainly limited to patients with the largest blood clots.

How Was the Study Designed?

ATTRACT was a Phase III, multicenter, randomized, open-label, assessor-blind, controlled clinical trial (see full study protocol). The study is registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT 00790335) and was performed under IND 103462 from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (for the off-label use of tissue plasminogen activator). Patients with symptomatic proximal DVT that involved the iliac, common femoral, and/or femoral vein (i.e. large blood clots of the leg or pelvis) were randomized (randomly chosen like the flip of a coin) to either receive or not receive a clot-busting treatment called Pharmacomechanical Catheter-Directed Thrombolysis (PCDT). All patients, whether or not they received PCDT, received standard treatment for their DVT, consisting of blood-thinning drugs and elastic compression stockings.

Patients were followed for 2 years, and had the following clinical outcomes rigorously assessed: the development and severity of PTS (Villalta scale, Venous Clinical Severity Score); change in health-related quality of life from baseline (VEINES-QOL/Sym and SF-36 measures); change in initial leg pain (Likert scale) and swelling (calf circumference) from baseline; safety (bleeding, recurrent DVT, death during follow-up), and costs. An ultrasound substudy was also performed in approximately one-sixth of the overall cohort to evaluate whether PCDT influenced rates of valve reflux and late venous obstruction, and whether this influenced PTS and quality of life.

Who Conducted the Study?

The ATTRACT Trial has been hailed as featuring an unprecedented degree of collaboration among international leaders in DVT research, education, and clinical practice from a broad range of clinical and non-clinical disciplines. The main collaborating institutions that ran the study were Washington University in St. Louis, MO (Clinical Coordinating Center), McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario (Data Coordinating Center), Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, MA (VasCore, Vascular Ultrasound Core Laboratory), and the University of Missouri – Kansas City, MO (Mid America Heart Institute, Health Economic Core Laboratory).

A full list of study contributors, including institutions, investigators, and research teams at the 56 Clinical Centers that enrolled patients in the study, can be found in this Online Supplement.

Study Leadership – Steering Committee

- David Cohen, MD, MSc (University of Missouri – Kansas City) – Co-Chair, Economic Core Lab

- Anthony J. Comerota, MD (University of Michigan) – Site Monitoring & Enrollment Committees

- Samuel Z. Goldhaber, MD (Harvard Medical School) – Chair, Steering Committee

- Heather Gornik, MD (Cleveland Clinic) – Chair, Medical Therapy Committee

- Michael R. Jaff, DO (Harvard Medical School) – Chair, Vascular Ultrasound Core Lab

- Jim Julian, MMath (McMaster University) – Lead Biostatistician

- Susan Kahn, MD, MSc (McGill University) – Chair, Clinical Outcomes Committee

- Clive Kearon, MB, PhD (McMaster University) – Chair, Data Coordinating Center

- Stephen Kee, MD (University of California, Los Angeles) – SIR Foundation Representative

- Andrei Kindzelski, MD, PhD (National Heart Lung and Blood Institute) – Project Officer

- Lawrence Lewis, MD (Washington University in St. Louis) – Chair, Enrollment Committee

- Elizabeth Magnuson, ScD (University of Missouri – Kansas City) – Economic Core Lab

- Timothy P. Murphy, MD (Brown University) – Operations and Site Monitoring Committees

- Mahmood K. Razavi, MD (St. Joseph’s Hospital) – Chair, Interventions Committee

- Suresh Vedantham, MD (Washington University in St. Louis) – National Principal Investigator

Who Funded and Supported the Study?

P Clot Trial Procedure

The ATTRACT Trial was sponsored by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), a part of the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH), via grants U01-HL088476 (to Dr. Suresh Vedantham from Washington University in St. Louis) and U01-HL088118 (to Dr. Clive Kearon at McMaster University).

P Clot Trial Meaning

The NHLBI provides global leadership for research, training, and education to promote prevention and treatment of heart, lung, and blood diseases and enhance the health of all individuals so that they can live longer and more fulfilling lives. The NIH, a part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, is the primary Federal agency for conducting and supporting medical research. Helping to lead the way toward important medical discoveries that improve people’s health and save lives, NIH scientists investigate ways to prevent disease as well as the causes, treatments, and even cures for common and rare diseases.

Four companies provided supplemental support to the study: Boston Scientific Corporation (funding), Covidien (now Medtronic) (funding), Genentech (a Roche Company, donation of tissue plasminogen activator), and BSN Medical (donation of elastic compression stockings). The Society of Interventional Radiology (SIR) Foundation played a pivotal role in the genesis of ATTRACT and its Clinical Center network, and actively collaborated with the research team to educate physicians, the public, and the media about the trial, and to disseminate the study results.